Hey, hey! Kyra Kyle here. We’re bringing back an old series: Top 5 Tabletop Games. The lists prior to this one (the 30s and 40s-50s) had fewer titles to choose from during their time periods and served as the best board games of that decade instead of a year. But the 1960s produced so many popular and great games that we split it into two Top 5 lists. One for the beginning of the decade (1960-1964) and another for the end of the decade (1965-1969). We’ll publish the second list next week.

So much time has passed since our last Top 5 Tabletop Games that we may need to reiterate the ground rules before we get started.

1: Cultural relevance plays as much of a factor as overall quality. A game might make a list that doesn’t hold up to others of its type, but you must admit the game is everywhere.

2: Only one game from a franchise makes the list. This will become more of an issue the closer we get to games with expansions.

3: Longevity plays a role, too. A game doesn’t have to fly off the shelves today, but it had to have some widespread appeal for a decent time.

5: Hi Ho! Cherry-O (1960)

Woo! Hi Ho! Cherry-O just barely made this list. Perhaps I should run a survey and see which tabletop games were people’s first games. Hi Ho! Cherry-O may be near the top of that list.

Each player begins with an empty basket and 10 cherries on their tree. Players take turns spinning the spinner and performing the actions they spin. The first player to collect all the cherries from their tree and yell “Hi Ho! Cherry-O” wins. Simple premise. Easy rules to explain and understand.

And yet, mathematicians used a Markov chain to determine how long a game of Hi Ho! Cherry-O would last. Who knew that picking cherries could get so intense?

4: Focus (1963)

Focus is the first and not the last Sid Sackson game that will make these lists. It’s an abstract strategy game where players move stacks around a checkerboard with the three squares in each corner removed. Stacks may move as many spaces as there are pieces in the stack. Players may only move a stack if the topmost piece in the stack is one of their pieces. When a stack lands on another stack, the two stacks merge. Basically, one tries cornering their opponent(s) into no longer having moves.

Focus also happens to be an early recipient of the Spiel des Jahres, the German Game of the Year (1981). This award elevated the quality of board games that came from Germany after its inception. Sackson did the same for the board game industry prior to this award, which is why, in part, Focus earned this honor. That and Focus is a great game that has inspired countless tabletop game designers.

3: Mouse Trap (1963)

How many of you have built the Rube Goldberg-like mouse trap for this game and never played it? Show of hands. Mouse Trap has players building the least efficient trap to catch a mouse. But the game doesn’t play anything like it did back in 1963. The original Mouse Trap required an opponent to land on the “cheese” space by exact count and the player to land on the “turn crank” space by exact count for a chance that the clunky Mouse Trap might work and eliminate a player.

Fast forward 12 years and the game play surrounding the trap was retooled by Sid Sackson. Hey, there’s that name again. Sackson added the cheese-shaped tokens that allowed players to move themselves or other players or turn the crank of the machine. Sackson streamlined a game that could take several hours into one that can be played in under an hour.

Mouse Trap may lean heavily on a gimmick, but one can’t question its staying power.

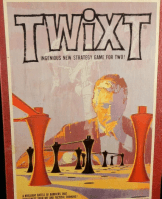

2: TwixT (1961)

TwixT began as a paper and pencil game in 1957 by Alex Randolph. And in 1961 Randolph was commissioned along with Sid Sackson (Hey, there’s that name again) to start a games division. TwixT was one of Randolph’s first produced games. It was even short-listed for the first Spiel des Jahres (Hey, we know that award, too) in 1979.

Players take turns placing pegs of their color into a 24×24 square grid of holes. One tries to move from one end of the board to another, connecting one’s pegs by making knight moves (in Chess). You cannot cross two connected pegs, so it’s possible to block your opponent’s progression and that’s what you’ll want to do. TwixT has a bunch of strategy but is easy enough that young children can play. No wonder it was inducted into the Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts & Design’s Hall of Fame along with Randolph.

1: Acquire (1964)

I wonder who designed Acquire. Wait! It’s Sid Sackson. Again. In Acquire, players attempt to earn the most money by developing and merging hotel chains. When a hotel chain that a player owns stock is acquired by a larger chain, players earn money based on the size of the acquired chain. Player will liquidate all their stock at the end of the game and whoever has the most money wins.

Acquire was also short-listed for the first Spiel des Jahres in 1979 and was inducted into the Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts & Design’s Hall of Fame along with Sid Sackson. The tabletop gaming community owes a lot to both of these incredible game designers.

My aunt Erma had a copy of Acquire but lost the rulebook, so I made up my own rules to this game. So, Acquire holds a special place for me personally. I may be a little biased with this number 1.

But did we get the list right, for the most part? Let us know in the comments. And wherever you are, I hope you’re having a great day.

Check out the other lists from this series:

Top 5 Games prior to the 1930s

Top 5 Games from the 1930s

Top 5 Games from the 1940s-50s

Top 5 Games from the Late 1960s

Top 5 Games from the Early 1970s

Top 5 Games from the Late 1970s

Top 5 Games from 1980-1981

Top 5 Games from 1982-1983

Top 5 Games from 1984-1985

Top 5 Games from 1986-1987

Top 5 Games from 1988-1989

Top 5 Games from 1990-1991