Board gamers tend to see the same game mechanisms from one game to another, so it made us wonder which board game mechanisms are the most common. Knowing this will allow new players (and older players) the kinds of game mechanisms they can expect to find in board games. Fortunately, the data required for this list is a lot easier to obtain and compile than our most common fantasy creatures post last year. Thank you, Board Game Geek.

Hey, hey! Kyra Kyle here. I checked the hundreds—and I mean hundreds—of game mechanisms listed on Board Game Geek and ran quick searches to see how many games are listed on the site with each mechanism. At the time of this post (early 2025), Board Game Geek caps its search results to the top 5,000 games that fit a search’s criteria. Almost thirty of the hundreds of game mechanisms searched yielded 5,000 results, which means each of these mechanisms could be in hundreds, if not thousands, of more games. Yikes!

Some mechanisms found in at least 5,000 games are movement-based or mundane, like “it uses paper and pencil” or “dice rolling,” which means that the game includes dice. We won’t bother covering those game mechanisms. But that still leaves dozens of interesting game mechanisms for multiple posts like this. We’ll cap this first post to ten of the most used game mechanisms. This doesn’t include mechanisms with over 3500 games like worker placement. I think this means that we need more worker placement games. I like worker placement games, so it’ll probably make the next list. But which board game mechanisms made this list? Let’s find out.

Action Points

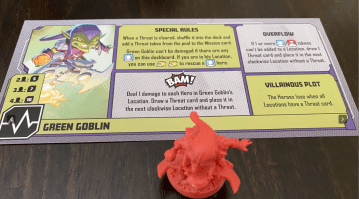

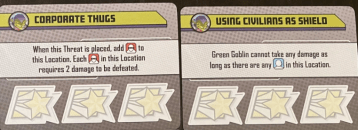

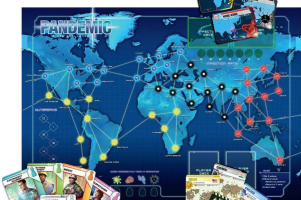

Board games that use action points grant players a supply of action points each turn. Players may choose to use these action points in a variety of ways, typically there’s a list of options. Usually, players can spend their points any way they please. You could take the same action multiple times (or even take the same action for their entire turn) or mix and match actions from the player’s options. The options may cost the same number of action points, or their point value can differ.

Thoughts

Action points give players agency. Your turn can look completely different than your opponent/teammate. I mention “teammate” here because I’ve seen several cooperative board games use action points. The agency (giving players a meaningful choice, which affords those players power) granted by the action points game mechanism is why this game mechanism is so popular in board games. Everyone likes to feel as if they have some control.

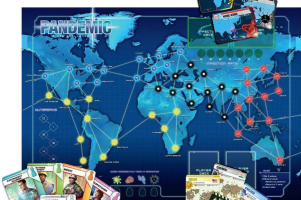

Games that use this mechanism

Pandemic, Takenoko, Horrified, Dinosaur Island, and Sleeping Gods

Deck, Bag, and Pool Building

Usually, games that include deck/bag/pool building begin with each player owning a similar deck of cards (if the game uses cards) or a similar number and type of chits or dice (if the game uses a bag or pool). Over time, players will acquire new cards (or the like) and add them to their deck, bag, or pool. Eventually, each player will own a deck or bag unique to them. Each player will use their deck to pursue their path toward victory.

Deck building differs from deck construction (another popular game mechanism) because players build their deck during the game, while decks within a deck construction game have players build their decks before playing.

Thoughts

When done well, deck, bag, and pool building games offer endless replays, due to the countless ways players can build their decks. The best players are the ones who can adapt. They’re the ones who can see patterns form with the cards and what may counter an opponent’s deck. Because of this, veteran players of specific deck building games can exploit their knowledge to gain an edge, but there is a hint of randomness. You must draw into what you need. This randomness evens the playing field a touch.

Games that use this mechanism

Dominion, Orleans, Challengers!, Thunderstone, and Aeon’s End

Hand Management

Games that use hand management reward players for playing their cards in certain sequences or groups. The optimal sequence may vary depending on board position, cards held, and cards played by opponents. Managing your hand means that you gain the most value out of available cards given your current circumstance. Often, these cards have multiple purposes, so this further complicates an “optimal” sequence.

Thoughts

Hand management could’ve been dismissed as a mundane game mechanism. Any game that includes a hand of cards will innately have hand management. But hand management is unique from this subset of board game mechanisms. Other mechanisms like dice rolling and paper and pencil mean that these physical elements exist within a game. Hand management suggests that players must take an active role in this game mechanism. And as the description says, this game mechanism is rewarding when players find the perfect sequence for their circumstances. Hand management also happens to show up the most on Board Game Geek’s Top 10-ranked games.

Games that use this mechanism

Brass: Birmingham, Ark Nova, Gloomhaven, Terraforming Mars, and Twilight Struggle

Open Drafting

Board games using open drafting have players pick (or purchase) cards (or tiles, dice, etc.) from a common pool to gain an advantage or assemble collections that meet objectives. Since the drafting occurs in the open, the identity of these cards (or other similar item) is known to other players. Drafting gives players a choice and the ability to gain a card another player may want, denying them something they wanted.

Open drafting differs from closed drafting, which is also known as “select and pass.” Everyone can see the item you gain as you obtain it.

Thoughts

Open drafting provides an immediate back-and-forth between players. Since you know what your opponents select each turn, and your opponents know what you select, a meta-game (or game within the game) takes shape. Like the two previous game mechanisms, players must adapt to what options are available during their turns and what they believe their opponents are planning to do. This back-and-forth can lead to table talk (talking between players at the table about the game they’re playing) and builds tension.

Games that use this mechanism

The Castle of Burgundy, Everdell, Wingspan, Blood Rage, and Splendor

Pattern Building

Games that use pattern building task players with configuring game components to achieve sophisticated patterns. These patterns can score points or trigger actions. Unlike most other game mechanisms on this list, pattern building is synonymous with another game mechanism on this list (tile placement), which we’ll cover later. Often, players want to link similar component types together or as mentioned above, create elaborate patterns.

Thoughts

Pattern building is the most puzzle-based mechanism on this list. The shifting tiles (and sometimes cards) lead to tasty combinations. So many games that fall into this category can be visually stunning. If you must build a pattern, the pattern should be easy on the eyes. This leads to why a lot of modern games use pattern building. Puzzle + Beautiful Patterns = Popular Game.

Games that use this mechanism

Azul, Cascadia, The Isle of Cats, Harmonies, and Welcome To…

Push Your Luck

With push your luck games, players decide between settling for existing gains or risking them all for further rewards. Games of this type feature an amount of output randomness or luck. We mention the two types of luck in a previous post (link to the two types of luck, input and output luck here). Players focus on progressing and maximizing their results. But typically, the stakes rise. If things go wrong, you lose it all.

Thoughts

Push your luck can add spice to an otherwise dull series of mechanisms. Double or quit, keep going or stop, cash your gains or bet them. This isn’t a new idea. Plenty of gambling games, like Blackjack, make use of the push your luck mechanism. Heck. Many of you may have read the description and immediately thought of Blackjack. Gambling games aren’t the only games that use the push your luck mechanisms. In fact, board games that use the push your luck mechanism can be good for gamers who want the feeling of gambling without involving any real-world money. These games can create a similar rush.

Games that use this mechanism

Heat: Pedal to the Metal, King of Tokyo, The Quacks of Quedlinburg, Lost Cities, and Return to Dark Tower

Roll/Spin and Move

Roll/spin and move games deploy the use of dice (rolling) or spinners (spin) and then move in some capacity. Historically, players roll or spin and move their playing pieces per the number (or other result) rolled (or spun). Countless classic board games have used the roll/spin and move mechanism as a key ingredient. Most people outside the board game community may expect roll/spin and move within all board games. A roll/spin and move game is what most people outside the board game community think of when they think of board games. Board games like Monopoly and The Game of Life popularized roll/spin and move.

Thoughts

People within the board game community often use “roll/spin and move” as a derogatory term. People who do this imply that there is no thought involved with this mechanism. While this is the case for a lot of older games (there are some exceptions like Backgammon), modern board games have taken the roll/spin and move mechanism into new territory. I agree that players lose their agency (power and ability to make meaningful choices) if they must roll or spin and move the spaces indicated on a die (or spinner) with no additional input. But some newer games add other forms of movement to this formula. Other newer games allow players to manipulate the results. Even more modern board games have players roll dice ahead of a turn and then assign the dice results to an array of actions.

Roll/spin and move isn’t an inherently poor mechanism. How a designer uses roll/spin and move makes all the difference. The key to making roll/spin and move work is maintaining a player’s agency.

Games that use this mechanism (well)

Jamaica, Camel Up, Formula D, Stuffed Fables, and Colosseum

Set Collection

Board games that use the set collection mechanism often make the set worth points. The value of the items is dependent on being part of a set. These sets can either be the quantity of a specific item type or a type’s variety. In some cases, board games can use contracts that urge players to pick up certain items to fulfill the contract.

Thoughts

The set collection mechanism breeds external tension between players. One may pick up a resource or item to prevent an opponent from fulfilling a contract or gaining more points by having more of a resource (or item) than anyone else. Or two players may fight each other for the ability to pick up these items because they both want to accomplish the same goal.

The set collection mechanism by itself may fall flat, but set collection seldom shows up on its own. Set collection complements a host of other board game mechanisms. It can give a built-in reason for players to choose a course of action or a sudden gain of a lot of one item or an array (variety) of items can tempt players to change their strategy or tactics. Board gamers often overlook the value of the set collection mechanism, but several popular games use set collection.

Games that use this mechanism

Great Western Trail, Ticket to Ride, 7 Wonders, Lords of Waterdeep, and Tokaido

Tile Placement

Tile placement games feature placing a piece (or tile) to score victory points or trigger actions. Usually, adjacent pieces or pieces in the same group/cluster or keying off non-spatial properties like color, a feature’s completion, and cluster size trigger the action or scoring. Pattern building often accompanies tile placement, but there are some notable exceptions, specifically, games that use modular boards and exploration.

Thoughts

While some tile placement games (like 1986’s Labyrinth and Dominos) existed before the modern board game boom (the mid-1990s and beyond), tile placement (and a few other mechanisms like worker placement and deck building) have taken the place of the roll/spin and move mechanism as modern board games’ dominant game mechanism. Just because the tile placement mechanism can be found in countless modern board games doesn’t mean that each game uses the mechanism the same way. Some games have a shared space for players to place tiles. Other games give each player a private building space. And several games do a little bit of both. Despite tile placement’s explosion after Carcassonne popularized it as a central game mechanism in 2000, tile placement remains a vibrant board game mechanism.

Games that use this mechanism

Carcassonne, A Feast for Odin, Galaxy Trucker, Betrayal on House on the Hill, and Castles of Mad King Ludwig

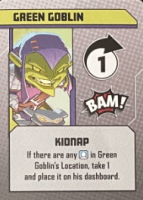

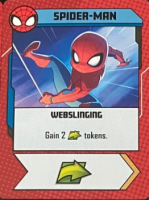

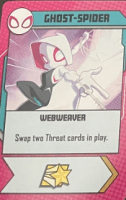

Variable Player Powers

The variable player powers game mechanism grants different abilities or paths to victory to each player. Each player has a unique power. Games that use variable player powers reward players who exploit their unique abilities while compensating for their abilities’ shortcomings.

Thoughts

The variable player powers game mechanism is perfect for any player who wants to stand out from their opponents. Because each character (or faction) within the game plays differently from each other, games that use variable player powers have a lot of replay opportunities. On a similar note, players may gel with a specific power over another one so playing a second game and trying a different player power could lead to better results.

Unlike other game mechanisms on this list (except for deck building and Dominion), variable player powers haven’t been around as long. Games that use the variable player powers mechanism also dominate Board Game Geek’s Top 10 ranked board games.

Games that use this mechanism

Gloomhaven, Twilight Imperium: Fourth Edition, Dune: Imperium, Pandemic Legacy: Season 1, and Cosmic Encounter

Closing Thoughts

This was a longer list than I expected. It would be even longer if I didn’t cut the list of common board game mechanisms in half or into thirds. Let me know if you’d like to see more lists like this in the future.

Looking at the board game mechanisms listed on Board Game Geek allows for a macro view of the board game hobby. We can see trends. We can examine what makes a board game mechanism popular. A lot of these board game mechanisms grant some form of player choice or player empowerment. But that’s what I think. What do you think? Let us know in the comments.

Geekly may have another series in the offing. We’ll craft another set of surveys and reach out to board game designers to discover their thoughts about each of these game mechanisms (and game mechanisms that may find themselves on a future list like this one). I hope you found something useful in the post. And wherever you are, I hope you’re having a great day.