Spring Meadow is the grand finale of Uwe Rosenberg’s puzzle trilogy of games. It follows 2016’ Cottage Garden and 2017’s Indian Summer. The complexity of this game—the most interactive between the players in the trilogy—is set in between those two games. Hey, hey, Geekly Gang! Kyra Kyle here with another tabletop game review. We’ll be placing oddly shaped polyominoes on wintery player boards in today’s game review, Spring Meadow. Uwe Rosenberg’s final game of his puzzle trilogy marks the end of a harsh winter, and the first delicate flowers bloom. Can you have the lushest meadow? We’ll get to Spring Meadow’s review in a bit, but first, let’s talk about the less picturesque elements of the game and discuss Spring Meadow’s credits.

The Fiddly Bits

Designer: Uwe Rosenberg

Publisher: Stronghold Games; Pegasus Spiele; Edition Spielwiese

Date Released: 2018

Number of Players: 1-4

Age Range: 8 and up

Setup Time: 5-10 minutes

Play Time: 15-60 minutes

Game Mechanisms

Grid Coverage

Pattern Building

Tile Placement

Game Setup

We’ll be paraphrasing the Spring Meadow rule book. The setup is succinct and easy enough to follow.

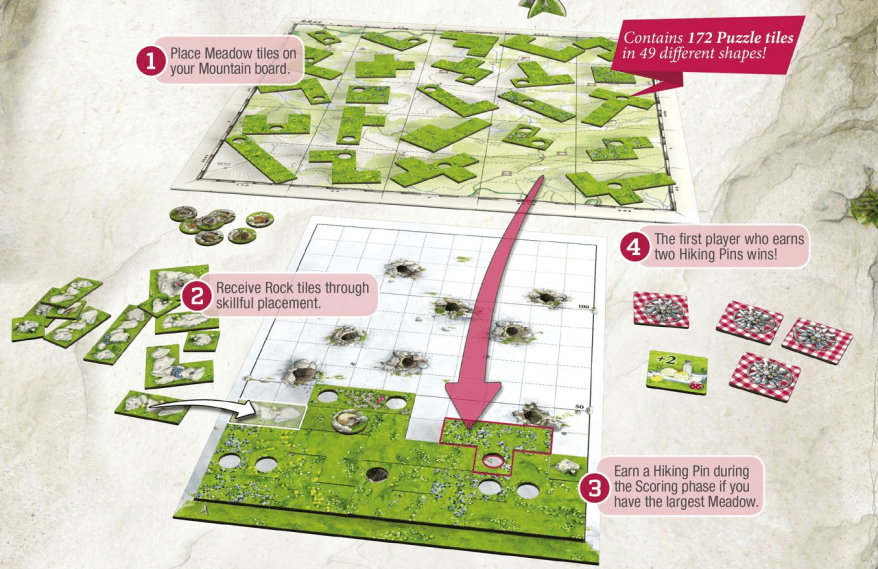

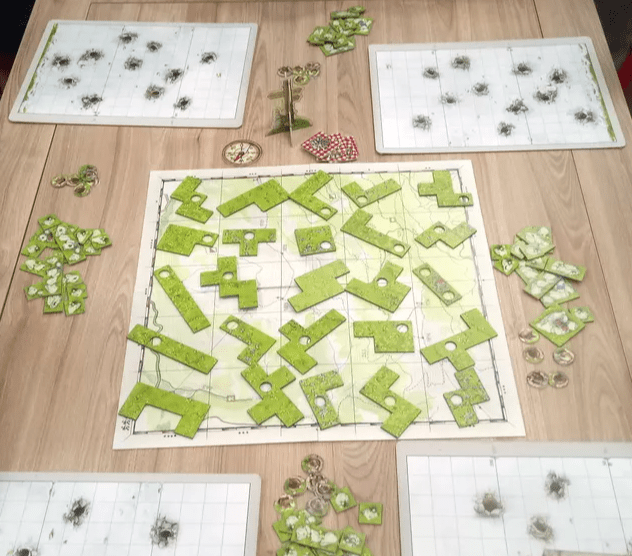

1) Place the double-sided Hiking Map (shared board featuring the offering of polyominoes) that corresponds to the number of players face up in the center of the table.

2) Shuffle all Meadow (polyomino) tiles and randomly place one on each of the 25 spaces of the Hiking Map.

3) Return the remaining Meadow tiles to the box. You will need them later to refill the Hiking Map.

4) Place the Rock tiles, Marmots, Picnics/Hiking Pins, and Compass within reach of the players in a common supply.

5) Place the Signpost next to the player count icon on the Hiking Map.

6) Shuffle the double-sided Mountain boards and give one to each player. Orient the Mountain board with the arrow pointing up.

7) Randomly select a starting player. Each successive player will take a Rock tile, the size of which will depend on the player count and the player order.

Game Flow

On a turn, the active player chooses 1 Meadow tile from the Signpost Path (noted by the Signpost pawn, you’ll either select from a row or column of polyominoes, depending on the Signpost’s orientation during your turn) on the Hiking Map. Place the tile on your Mountain board.

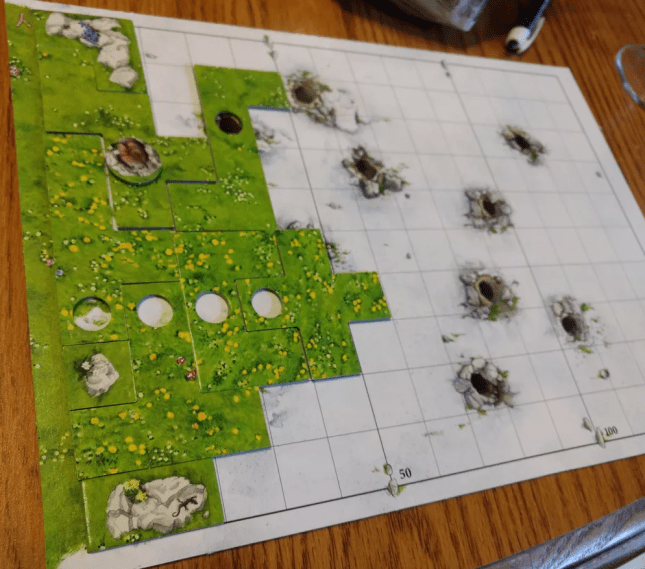

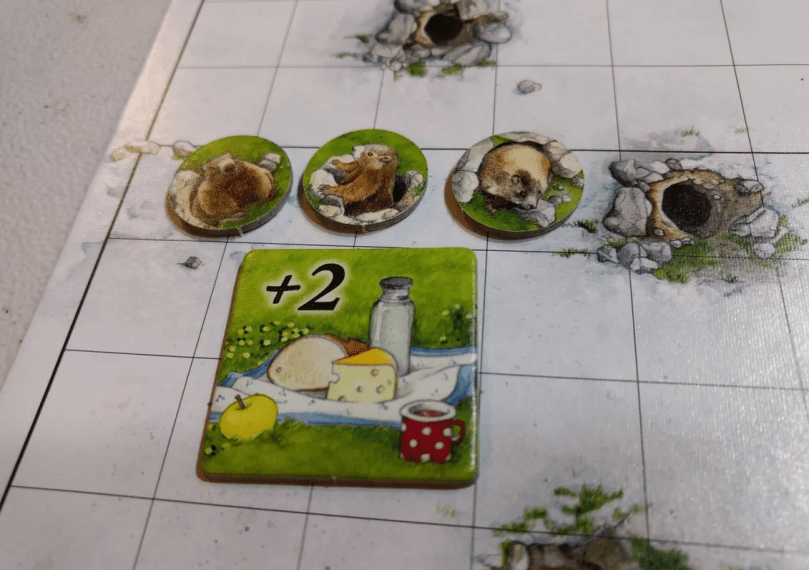

Pay attention to the Holes in the Meadow tiles and the Burrows on your Mountain board. Burrows will challenge your puzzle skills and placing adjacent Holes will allow you to place extra Rock tiles on your Mountain board.

If you wish to cover a Burrow, you must place a Marmot over a Burrow that has already been cleared.

When the Signpost stands next to a Signpost Path (column or row) on the Hiking Map containing zero or one Meadow tile(s), a Scoring phase is triggered.

Starting from the bottom of your Mountain board, count all covered spaces up to and including your first incomplete row to tally your score.

The player with the most points earns a Hiking Pin and must place Marmots over all their cleared Burrows (so they cannot score those Burrows again).

Once scoring is completed, refill the Hiking Map with randomly drawn Meadow tiles afterwards.

The first player to earn their second Hiking Pin wins the game.

Review

It took some time for me to get into Spring Meadow. I appreciated Spring Meadow’s theme. There’s something about the earth waking up from a cold winter. One of my favorite things to do during this time is to stop by the Platte River and hear the ice turn into slush and float on by. Spring Meadow gives me those vibes. And I love polyominoes in general, and Spring Meadow uses them in interesting ways. Kind of like a competitive Tetris, where you want to fill the board with as many blocks as possible. But Spring Meadow has a steep learning curve, and if you play with a new player, that can derail the game.

Sure, at one point, I was that new player. The person who taught me the game had a fun enough time, but he didn’t really find enjoyment in playing Spring Meadow until me and another player from my gaming knew had played a handful of games. He told me as much. And I found the same to be true. Spring Meadow feels unforgiving as the “new player,” but as an “experienced player,” I felt as if I was taking advantage of someone else.

While Spring Meadow’s player (Mountain) boards can be oriented in landscape or portrait, I prefer portrait. There isn’t much difference between the two orientations, but portrait clicks a little better with me. Other players in my gaming group said the opposite, so there’s a chance portrait or landscape orientation could benefit one player over another because of how different brains process information. This doesn’t lower Spring Meadow in my estimation, but I had to mention it.

I’m uncertain if Spring Meadow has a runaway leader problem. Certain plays of Spring Meadow devolve into a runaway leader, especially if you have a veteran player against noobs, but evenly skilled players can keep the game close. Still, I don’t think the Marmots covering cleared Burrows is a big enough penalty or catch-up mechanism. Player boards stay the same in between rounds, so if you’re ahead by fifteen points at the end of one round, all other players need to score fifteen more points than the leader during the second round. Good luck with that.

I could see gamers instituting an extra catch-up mechanism of handing players who are behind by more than five points, a one, two, or three rock tile. But that would be a house rule.

I also prefer Spring Meadow with fewer players. The three and four-player variants have one player selecting on the diagonal (instead of a row or column), but it’s the same player picking on the diagonal each time that happens. While picking the Meadow tile you want from a diagonal line may not add extra strategic value for that one player, it feels bad for the players who don’t get to choose from the diagonal, and choosing a tile from a diagonal line gives the illusion of more choice, because you’re literally picking your tile in a manner no one else can.

Despite any minor gripes I may have, I’ve enjoyed my time with Spring Meadow. It’ll be one of those games you’ll need to play multiple times to grasp the game’s nuanced strategy. Fortunately, games of Spring Meadow don’t take that long. Fifteen minutes per player is short. This is another reason why I like playing Spring Meadow with fewer players. A two-player game takes up to thirty minutes. Nice!

Too Long; Didn’t Read

Spring Meadow may have a runaway leader problem, and veteran players have a decided advantage over noobs. But I love the theme and the game uses polyominoes in intriguing ways. Spring Meadow is one of those games you’ll need to play more than once to grapple with its nuanced strategy. Thankfully, games of Spring Meadow don’t take long: fifteen minutes per player.