Happy Friday, Geekly Gang! Kyra Kyle here with another game design brain dump. Our first of the year. Yay! Recently, I watched Netflix’s Delicious in Dungeon. I even shared it during one of our Watcha Watching posts. And instantly, I had a new idea for a board game. Well, Dungeon Chef is a variant of an old game design idea I had years ago. Let’s dish. Great. Now, I’m hungry.

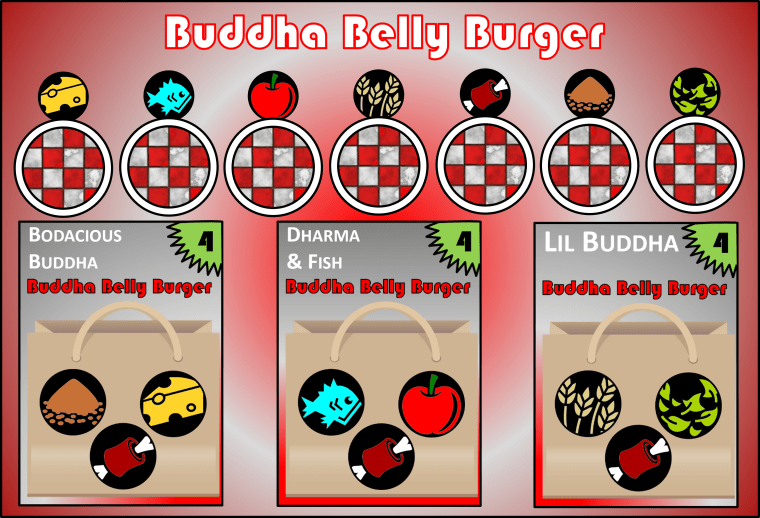

Above is an image of Food Court Hustle’s most recent iteration. Yes, Food Court Hustle was the game’s original name. Food Court Hustle was a card-drafting game where players manage restaurants in a food court. It played quickly, had plenty of Take That elements, and never took itself too seriously. I liked the concept and loved the name. But food courts are a little dated. That was the biggest complaint I heard from playtesters. The concept for Food Court Hustle’s game mechanisms was to give players more control during card drafting. Each round, players would choose one card to play (for its effect) and then choose a card to discard for its ingredients, only every player–not just you–gains the ingredient.

Like most card-drafting games, Food Court Hustle plays swiftly. Simultaneous play helps with game speed. Seriously. This was one of the few games I never felt the need to incessantly time. And that’s a good rule of thumb when designing games. Always time your games. You want to waste as little of your players’ time as possible. I’m not saying you can’t design a two-hour or longer epic board game, but the game should earn its play time. Getting back to Food Court Hustle, something beyond the theme was missing.

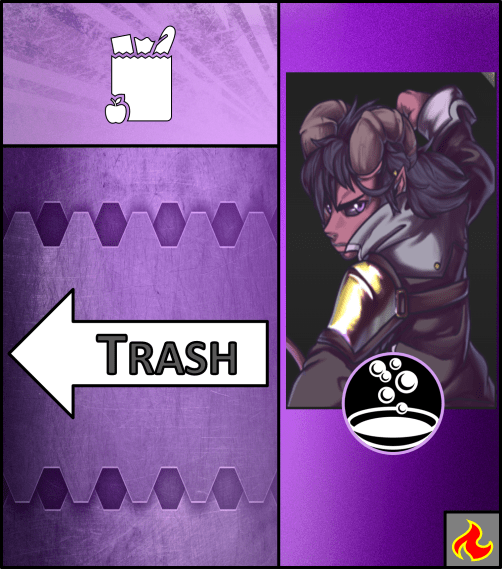

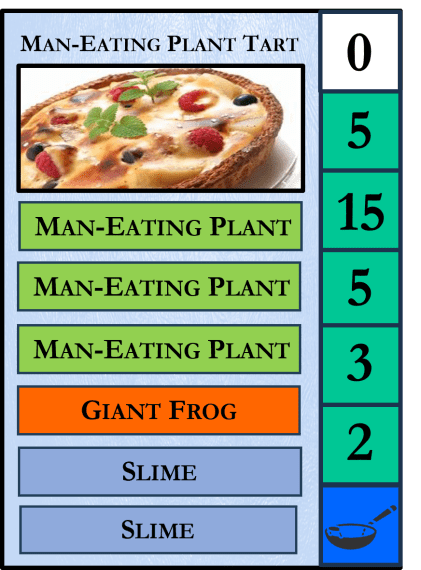

Tangent: the image above is Dungeon Chef’s player board, and the previous image was of a Food Court Hustle player board. The scale of these two images is almost what it should be, so I managed to shrink the player’s space while ditching customers. Yes. The original game included customer cards that wouldn’t always appear when players wanted to make a dish. Another gameplay gripe. You could have the ingredients and not be able to make a meal. Dungeon Chef gets rid of that layer of randomness. I also got rid of a lot of the Take That mechanisms and replaced them with global effects.

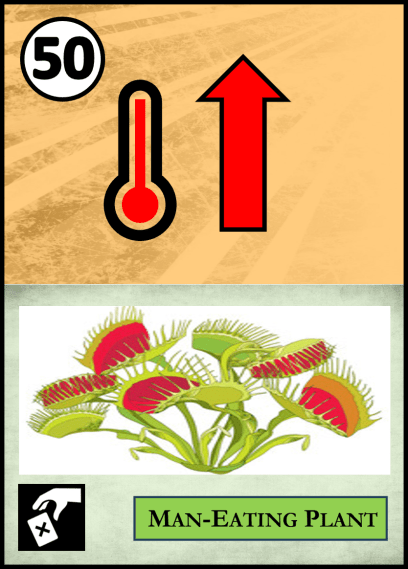

Above is a sample Dungeon Chef card. The top half is the action you may choose to play. The number indicates the player’s initiative for that turn. All cards in the three day decks are numbered 1-50. The higher the number, the quicker the action. I’ve seen players choose a card for its initiative, which is wild. The bottom half is the monster parts you may add to the communal ingredients. You wouldn’t be the only one gaining a man-eating plant. Everyone at the table gains a chunk of man-eating plant. And returning to the action on this card, you can turn up the temperature of the communal stove. That’s right. Most game elements in Dungeon Chef have global effects. Half the game is steering the game state in your direction.

Players can select a recipe by spending the ingredients on the recipe card. Then, they add the recipe to their player board, lining up the wok with the flame. And near the end of each turn, move the recipe card up the number of spaces indicated by the communal stove’s temperature. Players can take their active recipe off the stove and claim the victory points indicated on the card at any time. But beware, if a player leaves their meal on the stove too long, they could burn their meal, and it goes into the trash, costing them 10 points at the end of the game. Whoever has the most points at the end of three days wins. There’s little more to Dungeon Chef. I tried to keep it short, easy to understand, and stick to the Delicious in Dungeon theme as best I could.

We’ll see where this design goes. And who knows? Perhaps I’ll be at a gaming convention near you. Let me know which convention I should attend. If you made it this far, you’re awesome. We all know it. Thank you for reading, and wherever you are, I hope you’re having a great day.