I don’t care too much for Marvel Heroes, the miniatures game published by Fantasy Flight Games in 2006. It’s a little fiddly for my taste. There’s even a system in place to prevent a runaway winner, and while it does a good job of keeping the game close, it makes players feel a little less super.

I do like the game’s combat system. Leave it to a superhero game that depicts four superhero teams (X-Men, Avengers, Fantastic Four, and Marvel Knights) and their arch-nemeses to deliver the goods for combat.

Hi, it’s your uncle Geekly here and if you lasted long enough to not rage close this article, I’ll let you know how Marvel Heroes made Rock, Paper, Scissors interesting and fun.

I’ve talked briefly about Marvel Heroes in the past. It plays out well enough. Villains cause trouble in various places in New York and the various players (in charge of superhero teams) send their heroes to deal with said trouble. Usually, this means combat.

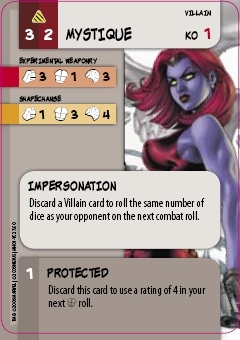

Each hero and villain have attacks—heroes always have three, but villains range from 1-3 attacks—they can make and each of these attacks has a value for attack, defense, and intelligence (intelligence equates more to initiative or speed than actual intelligence). Every attack is assigned to one of three tokens that a player can choose from and each player in the battle chooses which of their attacks they wish to use.

If you want to deal more damage, pick an attack that’s high in damage. If you’re worried about accepting damage, choose one with higher defense. Or if you don’t think you’ll get much out of a character (usually a low-level villain), pick one with a high intelligence so you can get in a quick shot before that character’s discarded.

The numbers indicated on the cards relate to the number of specialty dice you roll, so there’s always an element of luck added to the equation. It all boils down to an intriguing and layered take of rock, paper, scissors, but it’s done well. I just wish the rest of the game excited me as much as the combat. Still, with a few house rules it can be a great play.

What do you like most about the Marvel Heroes Strategy Board Game? What are the things you don’t like about Marvel Heroes? Maybe I’m a zombie to all things Marvel and just want to hate. You can chew my ear about it in the comments.