Hey, hey, Geekly Gang! Kyra Kyle here. Today, we continue our deep dive series on transgender representation in media. Dead End: Paranormal Park was our last deep dive in this series. We’re in the middle of the holidays, so I figured we’d cover a movie instead of a series. Nimona began as a 2015 graphic novel of the same name. Nimona highlights queer themes and fluidity of identity and how they oppose and subvert traditional controlling institutions and exclusionary systems. Wow! That sounded clinical. On a personal note, I identify as gender queer, something akin to nonbinary, so I can see myself in Nimona.

Nimona features a lot of great storytelling. Most main characters go through a satisfying arc that fits in the film’s overall theme. Early on, Nimona includes details that take on new meaning during a second viewing. This is always welcome. Specifically, dialogue like “Go back to the shadows from whence you came” hits differently each time in Nimona. In short, I haven’t seen an animated film this refreshing since Shrek and early Pixar movies. I could continue with how much I love Nimona’s story, but that’s not the purpose of this post. It’s time to break down Nimona’s transgender–and more specifically gender queer/nonbinary–representation.

Spoiler Warning

There’s no way I can cover this subject without major spoilers. Nimona is a Netflix original film; feel free to watch Nimona before reading. With that said, you’ve been warned.

Gender Non-Conformity and Other Queer Themes

We’ll view Nimona through various lenses, but before we get into how others view the title character Nimona, we need to discuss who Nimona is. Nimona is a shapeshifter.

Gender and Pronouns

Nimona doesn’t identify as any one gender, and because of that, I’ll be using they/them pronouns for Nimona. To be fair, Nimona avoids using pronouns at all. They’d probably say their pronouns are Nimona/Nimona. Perhaps Nimona’s pronouns are Ni/Nem. I’ll use Nimona instead of pronouns as often as I can. I wouldn’t want Nimona breathing fire on my scalp.

Nimona definitely doesn’t identify as a “girl.” Ballister constantly tries to dub Nimona as a girl. Most people who interact with Nimona use she/her pronouns if they want to be nice, but there are a few people who use the pronoun it for Nimona. The main antagonist, The Director, almost exclusively uses it for Nimona.

But I do like how Nimona seems unfazed by anyone misgendering them. Sorry if I used the wrong pronoun, Nimona. Not the scalp. Nimona goes with the flow, no matter which pronouns Nimona hears. Not even it/its upsets Nimona in an overt way. Even so, the pronoun it suggests the person using the pronoun sees Nimona as the one word Nimona hates to be called most: monster.

“Who has four thumbs and is great at distractions?”

Gender Fluid

I always loved Ranma’s ability (from Ranma 1/2) to switch from a masculine form to a feminine form with the touch of cool or warm water. This ability to change gender on a whim spoke to me when I was younger. I think it does for most gender queer people. In fact, Maia Kobabe (ey/em pronouns, pronounced like they/them with the “th” taken off) in eir graphic novel Gender Queer, mentions Ranma 1/2 by name when ey mentioned the media that inspired em to find emselves.

Ranma 1/2 was one of the stories Kobabe read when ey were still an egg. Note: “Egg” or “Egg Mode” is LGBTQ+ slang to describe transgender individuals who do not realize they are a transgender person yet, or are in denial about being a transgender individual. Extra Note: Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe is a must-read for gender non-conformity; Ranma 1/2 is a fun read in its own right.

Nimona’s ability to shapeshift into almost any living being taps into a similar primal desire for a gender queer egg. I like how Nimona uses its title character’s ability as an allegory. The entire film does a great job of tackling difficult issues through a fantasy setting. That’s the power of fantasy. Since Nimona can shift into almost living being, the film gives Nimona plausible deniability. In short, Nimona is gender queer coded.

And yet, there is one moment Nimona outright drops pretense, and I love it. When Nimona and Ballister go to the market to kidnap the Squire, Ballister chastises Nimona for shapeshifting. Nimona shifts to a gorilla. Ballister scolds Nimona. Then, Nimona shifts into Nimona’s typical form. Again, Ballister scolds Nimona. Nimona blows up. “You want me to shift, then you don’t want me to shift. Pick a lane.” Then, Nimona transforms into a little boy, and Ballister laments, “And now you’re a boy.” Nimona says, “I am today.” That’s a perfect moment for certain gender queer, gender fluid, or nonbinary people. Heck, I feel like that often. Too bad I can’t morph into a gorilla or dragon. I pick dragon.

Wouldn’t It Be Easier if You Were a Girl

Nimona has plenty of relatable moments. Nestled between a few action sequences, you’ll find two quieter moments: one on the subway train and the other in a shady part of town after Nimona and Ballister kidnap the Squire. The subway train scene is the first time Nimona and Ballister slow down to get to know each other.

Ballister: Can you please be normal for a second?

Nimona: Normal?

Ballister: I think it would be easier if you were a girl.

(I skipped a few lines) Nimona: Easier for who?

Ballister: Easier for you. A lot of people aren’t as accepting as me.

I’ve heard what Ballister said more than once. Wouldn’t it be easier if you picked one of the pre-approved genders? It would be easier for you. Translation: it would be easier for the person asking me the question, not easier for me. I know who I am, just like Nimona in this scene. Ballister would continue questioning how Nimona became Nimona. He wants to–in his words–know “what” he’s dealing with. Nimona feeds Ballister a story that turns out to be rooted in truth. The Kingdom’s ultimate hero, Gloreth, rejected Nimona when they were children.

Nimona could’ve always had their powers and doesn’t know where these powers originate. We never see anyone else with Nimona’s shapeshifting ability during the film. Others with Nimona’s abilities may also be in hiding. Or Nimona could be an original.

What is original is how Nimona describes their need to shapeshift. I’m sure I’ll mention this scene again, you’ve been warned. I love how Nimona describes shapeshifting. It comes close to how it can feel for a gender fluid person. “I feel worse when I don’t do it (shapeshift), like my insides are itchy. You know that second right before you sneeze? That’s close to it. Then I shapeshift, and I’m free.”

Nimona adds that they could not shapeshift, but they wouldn’t be living. This is why it isn’t easier if Nimona was a girl. Nimona is Nimona. Nimona needs to shift. It’s like asking someone not to sneeze when they have the urge. It hurts.

Nimona wears its queer identity on its sleeve, but it does so in subtle ways. This works to give Nimona a wider potential audience. Nimona does an incredible job of depicting life as a gender queer/gender fluid/nonbinary person. But Nimona explores more of the LGBT+ community.

Goldenloin and Boldheart

Nimona doesn’t shy away from Ballister Boldheart and Ambrosius Goldenloin’s homosexual relationship, and that’s great. Ballister and Ambrosius’s relationship is front and center. This works, especially after Ballister becomes a fugitive. The Kingdom views Ballister as a villain. Even though this role change is due to Ballister being framed for the Queen’s murder, it works on another level because of Ballister’s sexual orientation. Modern society isn’t that far removed from viewing homosexuality as deviant or even a mental illness. And many countries and religious/political zealots still view homosexuality as against the natural order.

Nimona drives this point home after Ballister defends the Kingdom. He claims that certain people are to blame for his getting ostracized, while Nimona insists the entire system needs to change. According to Nimona, the controlling institutions that run a Kingdom that would hunt a “villain” like Ballister and a “monster” like Nimona should be challenged. Amen, Nimona, amen.

Ballister is Still Repressed

Despite Ballister fully embracing his sexual identity, he’s still repressed. Nimona mentions how brainwashed Ballister has become after his knight training. Ballister seldom lets himself go until he’s spent plenty of time with Nimona. Nimona helps Ballister break out of his shell. Nimona affords Ballister the means to take a critical look at society and question everything. In short, Nimona lets Ballister “Unclench his mustache.”

We’ll talk about the wall and how no one, not even Ballister, has seen what’s on the other side of the wall. The people of the Kingdom as a whole are repressed.

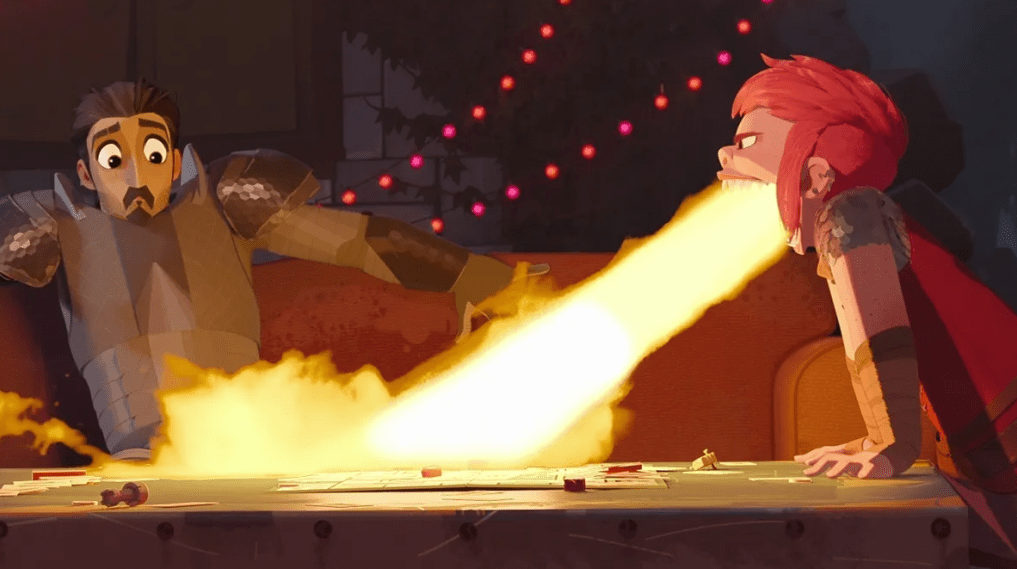

Other Queer Representation

Nimona includes so much queer representation. Here are a few short segments. During the closing credits, Nimona literally breathes a rainbow flag of fire. The film’s color scheme tends to lean toward the colors of the transgender flag: pink, white, and light blue. RuPaul is one of the news anchors. RuPaul for the win. “Sashay away” turns into “A knight who might not be right.” I’m probably missing dozens more queer references. Feel free to add any you found in the comments.

Fluid Identities Versus Controlling Institutions

Our next lens returns to that clinical definition I spewed in the opening: controlling institutions. Nimona shows how controlling institutions quell fluid gender identities in many ways. We’ll begin with the piece of dialogue I also mentioned near the beginning of this post. “Go back to the shadows from whence you came.” During Nimona’s opening, this line is given like a storybook. Think classic Disney animated films. Nimona’s opening has Warrior Queen Gloreth–or rather Nimona reading the story–heroically deliver this line. Eventually, we learn this line is what a child Gloreth says to her friend Nimona. This story thread shows how fear of someone with a fluid gender (or gender queer) is a learned behavior.

Learning to hate differences

Gloreth and Nimona begin as friends. Gloreth doesn’t think it’s weird or dangerous that Nimona can transform into other creatures. In fact, Gloreth thinks it’s fun riding Nimona as a horse and swinging from tree to tree with gorilla Nimona. Gloreth doesn’t view Nimona as dangerous until her parents teach her to fear Nimona.

Society has a nasty way of perpetuating stereotypes and demonizing people who differ from societal norms. The fear of going against societal norms keeps people in check. Societal norms (or peer pressure on an institutional level) keep people under control. Nimona does a great job of showing how society can demonize others, while also shining a light on a Kingdom ready for change. Sure, Nimona tells us and Ballister (Nimona’s “boss”) that once someone sees you one way, they’ll never see you as anything else, but Nimona shows us how Ballister changes how he views Nimona. And I like how Ballister is the first commoner turned knight, a position historically held by nobility in the world of Nimona. This shows the Kingdom is ready for change.

People have a habit of hating people who are different. Divorced from outsider influence, Gloreth accepts Nimona. She even revels in the two’s differences. Gloreth’s parents fear Nimona because of their differences. Gloreth attempts to stand up for her friend, but she can’t prevent the village from attacking Nimona. The mob inadvertently sets their own village on fire. I like the imagery of attacking Nimona, resulting in attacking oneself. Humanity grows the more we allow individuals to be themselves. We all have our differences; we should revel in them. As the village burns, Gloreth picks up a toy sword and utters the line, “Go back to the shadows from whence you came.” This line hits differently each time it shows up in Nimona. During the opening, the line is told like a warm and familiar fairy tale. Here, the line is cold and heartbreaking. Relegating queerness to the shadows is one of the ruling institutions’ insidious methods of control.

Life in the Shadows

When they targeted the Institute for Sexual Research (Institut für Sexualwissenschaft), Nazis burned decades–if not over a century–of books on transgender studies in 1933. Modern radical religious groups and far-right political zealots view transgender people as a fad, something that hasn’t existed for long, even though transgender and gender queer people predate Nazis by at least several decades. Even today, governments sign executive orders, legally limiting the number of genders to only two. Thank you, Trump.

In truth, gender non-conforming people pre-existed the current era. Society and the ruling factions have a knack for forcing gender non-conforming people into the shadows. Ancient Egypt recognized three genders. Pharaoh Akhenaten (either 1353-1336 BCE or 1351-1334 BCE) is depicted with feminine and masculine features. Gender non-conforming people have always existed.

Going back to Nimona’s opening cinematic, after Nimona finishes the storybook introduction, the movie fades to black, and text reads, 1,000 Years Later. Yep. We’ve been here for over a thousand years. That tracks.

Obviously, it stinks for gender non-conforming people to be relegated to the shadows, but by doing so, society hurts itself. Refusing to recognize gender non-conforming people narrows one’s worldview. This line of thinking traps people into small boxes. Society withers when it doesn’t recognize more of its citizens. The world is a less colorful–or, as Nimona would phrase it, metal–place. And that’s why I love the image of the thousand-year-old village attacking Nimona and, in turn, attacking themselves. Such a great scene.

Nimona and Ballister outside the Wall.

A Life of Confinement

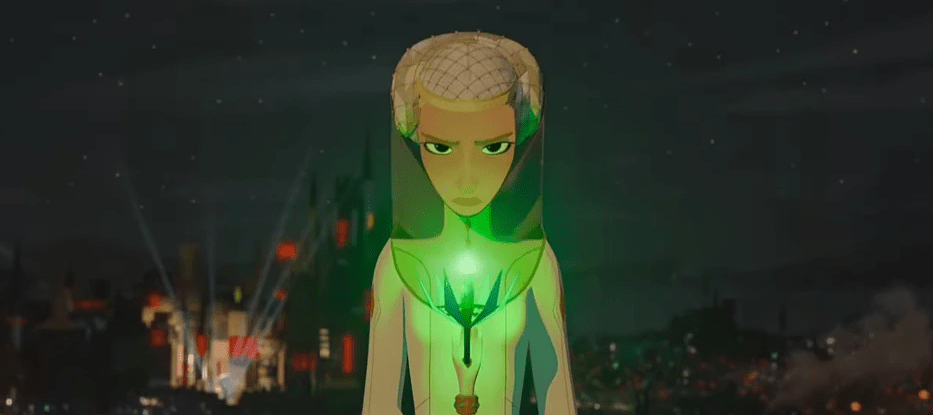

When Ballister asks what it feels like to shapeshift, Nimona shares that they feel worse when they don’t shapeshift, like their insides feel itchy. They liken the itch to the second before a sneeze. Shapeshifting makes them feel free. Shapeshifting is part of who they are. When asked what would happen if they held in the shapeshifting itch, Nimona says, they’d die. Nimona clarifies they wouldn’t “die” die, but they sure wouldn’t be living. I love this allegory for what it feels like to be gender non-conforming. Nimona’s way of living contradicts the Kingdom.

The Kingdom has built a wall from the outside world. The people of the Kingdom view everyone who’s different as a monster, especially Nimona. Everyone in the Kingdom is scared of what lies on the other side of the wall, even Ballister. When Nimona asks Ballister if he’s been beyond the wall, Ballister sarcastically says, Yes, I have, because I have a death wish. Nimona suggests that there may be nothing beyond the wall, and in the context of “nothing,” Nimona means to say nothing scary or threatening exists beyond the wall. Gloreth’s old village rests beyond the wall, as does a beautiful mountain scape and lake. The Kingdom sees none of this. The people of the Kingdom are trapped inside their fear.

I love the ending, where Nimona takes out a cannon aimed at the Kingdom (more on this in the next section), and the resulting explosion reveals what lies beyond the wall. Absolute beauty. The world is a better place when we accept others’ differences.

Tradition Is Greater than Life

The Director, Nimona’s main antagonist, illustrates a group of people who love tradition above life. The Director is a stand-in for religious and/or political zealots. She murders the Queen and frames Ballister for the Queen’s murder. This act sets the events of Nimona in motion. The Director blamed the Queen for knighting a commoner (Ballister). The Queen sullied the Kingdom’s good name for inviting anyone to become a knight (instituting a meritocracy instead of an aristocracy or plutocracy). In the Director’s mind, ridding the Kingdom of the Queen and Ballister could restore the “natural order.”

During Nimona’s final fight scene, the Director aims a cannon at Nimona. At this point, everyone in the Kingdom ceases to view Nimona as a threat, everyone except the Director. She repeatedly shows disregard for human life. By aiming a cannon at Nimona in this moment, the Director is aiming a cannon at the Kingdom itself. Thousands of people will die. To the Director, that sacrifice is worth it to maintain tradition. Only tradition matters. And this is where religious and political zealots turn deadly. It’s okay to have traditions, but placing tradition above life is an error we see humanity make throughout history. Funny how stories that feature a monstrous main character like Nimona reveal humanity to be the true monsters.

Subtle Discrimination

Throughout Nimona, we see children slaying monsters like Nimona: cereal commercials featuring dragons, robotic horse rides outside stores where children can slay various augmented reality monsters, and random slogans like “slay your thirst.” Sure, the Kingdom has plenty of overt discrimination against monsters, but the insidious examples prove more damaging. As Nimona says, children grow up to hate monsters. Hate is in the Kingdom’s DNA.

But Nimona also shows hope. It takes most of Nimona’s runtime, but Ballister learns to see Nimona for who Nimona’s true self.

Nimona even explores self-discrimination. Ballister struggles to accept parts of himself. He views the Kingdom as above reproach. Even after Ambrosius severs Ballister’s arm, Ballister defends Ambrosius’s action. We even catch a glimpse inside Ambrosius’s head as he tries to logic his way through cutting off his lover’s arm, because it was his training. Nimona marvels at how well The Institute brainwashed Ballister, but Nimona isn’t immune to self-discrimination.

Nimona attempts to take their life, a far too common occurrence for gender non-conforming people. Nimona mentions the subtle and casual discrimination against “monsters” earlier in the film’s runtime. I love how Nimona phrases their conflicted feelings.

Nimona: I don’t know what’s scarier. The fact that everyone in this kingdom wants to run a sword through my heart… or that sometimes, I just wanna let ’em.

Ballister stops Nimona from plunging a sword through their heart. Sometimes it only takes one person’s acceptance. Ballister is the one person for Nimona. Let’s end this segment with what Ballister says to Nimona in Nimona’s moment of crisis.

Ballister Boldheart: I’m sorry. I see you, Nimona. And you’re not alone.

Closing Thoughts

Nimona is a great watch. I didn’t mind rewatching it dozens of times for this write-up. I even shared it with my family on Parents’ Day (the last Sunday in July, which can be used to celebrate gender non-conforming parents). I don’t believe Nimona did too well when it first released on Netflix in 2023. The film struggled to reach the Top 10, but Nimona offers a singular experience on the streaming giant. If you missed it during its original release, you should give Nimona a watch. Even though it packs a ton of LGBT representation–transgender representation in particular–Nimona never gets preachy. It’s a fun movie.

This was another long, deep dive. I appreciate you reading this far. Let us know if there are any other great and maybe even not-so-great transgender representations in media you’d like to see us cover in the future. Thank you again for reading, and wherever you are, I hope you’re having a great day.