Hey, hey, Geekly Gang! Kyra Kyle here. We’re keeping the theme of Spooky Season alive with today’s post, but we’ll be taking horror or dark themes in a different direction. I’ll be up front, this post may meander more than usual. I didn’t know what to call these types of video games at first. Some of these video games could fall under the term “empathy games.” I mentioned some of these games in a previous post, but the prevailing term for the type of video game we’ll cover today is Walking Simulator. That name doesn’t do these games justice.

In fact, the Walking Simulator term is beyond reductive. It’s demeaning. All you’re doing is walking. This pejorative name reminds me of the terms Euro-Trash or Ameri-Trash board game from a decade or two ago. We’ll use the modern, friendlier terms for these board game types. Euro board games focus on mechanisms and balanced gameplay, while Amerithrash–they’re totally metal and they “thrash”–board games place more emphasis on theme. If you used the negative terms, you’re thumbing your nose at the other board game type. Many “hardcore” video gamers despise “Walking Simulators.”

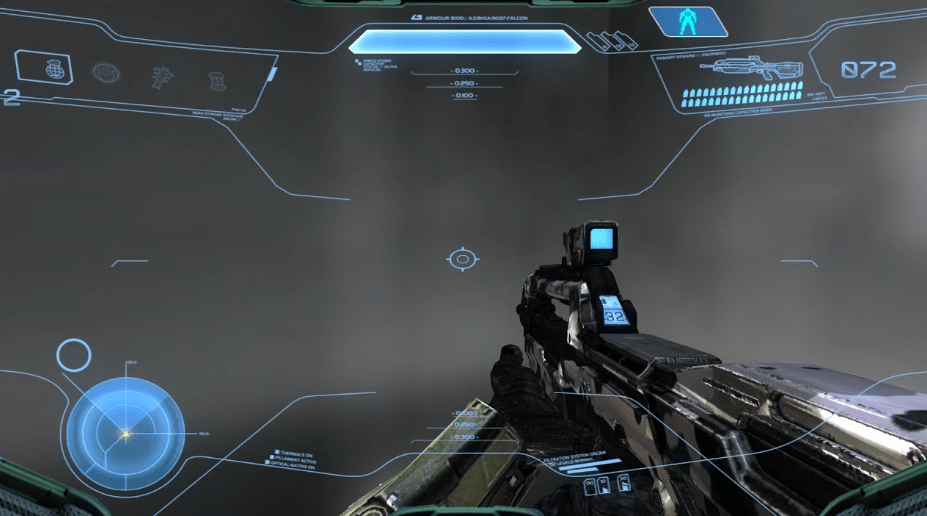

“Hardcore” video gamers not liking “Walking Simulators” makes sense. Video games sprang from the Military Industrial Complex. The first video games came from military facilities. Many “hardcore” video games promote wanton violence where the player kills countless enemies, feature “heads-up displays” one might find in a fighter jet, and some video games are even military recruitment tools. Of course, something quieter and geared toward empathy would ruffle the feathers of “hardcore” video gamers.

Getting back to Euro and Amerithrash board games, modern board games often blur the lines between these two game types. I reviewed Cretaceous Rails a couple of months ago, and it’s equal parts interlocking mechanisms and heavy on theme. Death Stranding notwithstanding, I don’t know if AAA video games have adopted enough from indie Walking Simulators, but that’s another topic. I told you I would meander. Despite the negative connotation (all you’re doing is walking), Walking Simulator is the term most people use. We’ll use that one. Since we’ll be dealing with psychological horror and/or darker themes, let’s call these games Dark Walking Simulators. Let’s cover a brief history with some of my favorite Dark Walking Simulators.

Prior to 2012: [domestic]

Point and click games could and sometimes do fall under the heading of a Walking Simulator, because they involve movement and interacting with the game world’s environment (which are hallmarks of Walking Simulators), and point and click games have been around since the early 80s. But we’ll begin this quick history with 2003’s [domestic] by Mary Flanagan. Flanagan repurposed the Unreal gaming engine to recreate a childhood memory of a house fire. One look at [domestic], and you can see why many consider it the first modern Walking Simulator.

In fact, the term Walking Simulator gained prominence in the late 2000s, perhaps as a direct result of [domestic]’s release. When you have the chance, you should check out Mary Flanagan’s website. She discusses at length her artistic choices while designing [domestic]. While she doesn’t have a link for a playable version of the game, Flanagan provides a two and a half minute video of [domestic]’s gameplay. There are so many innovative choices, like family photos and text constructing the walls of this 3D space, that we’ll see in future Walking Sims.

Dear Esther (February 2012)

First, Dear Esther is gorgeous. Look at that uninhabited Hebridean island. My partner and I made our way to one of the Inner Hebridean islands in Scotland, and this looks close. I could smell the salt air and the heather on the wind. Second, Dear Esther’s gameplay is minimal. I would almost classify this game as a Walking Simulator, but in the best possible way. An anonymous man reads a series of letter fragments to his deceased wife, Esther. Each location on the island reveals a new letter fragment. Players can unlock different audio fragments with each playthrough of the game, leading to a different narrative each time you play Dear Esther.

So, you’re literally walking from one area of the island to the next and listening to various letters, but the letters reveal more about the titular Esther’s life. Esther has passed under mysterious circumstances, and her husband is looking for answers. Dear Esther has a gripping narrative, but the tension comes from internal struggles. The Chinese Room developed this Walking Simulation classic, and this won’t be the last time we’ll see one of their games on this list.

The Unfinished Swan (October 2012)

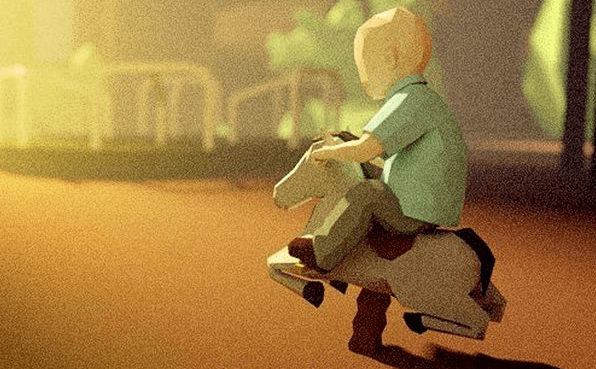

The Unfinished Swan marks Giant Sparrow’s first major release. It has a simple premise. Monroe is a young boy whose mother recently died. Monroe’s mother was a painter famous for never finishing a painting. Over 300 paintings and not one of them complete. The orphanage tells Monroe he can keep only one of his mother’s paintings, so he chooses his favorite, a swan missing its neck. The swan escapes, and Monroe follows it. Armed with his mother’s silver paintbrush, Monroe explores the painted world.

As you can guess, The Unfinished Swan ventures into magical realism. It tackles themes of loss. It puts players into the shoes of a young child, making sense of the world without their parents. The Unfinished Swan is the first of Giant Sparrow’s games to make this list. It showcases the studio’s knack for eclectic settings and its flair for the dramatic.

Gone Home (August 2013)

Gone Home puts the player in the role of a young woman returning from overseas to her rural Oregon family home to find her family absent and the house empty. She must piece together recent events to determine why her family’s home is empty. Gone Home is similar to the previous year’s Dear Esther, but the anonymous protagonist in Dear Esther knew that his wife had died. Katie, Gone Home’s protagonist, has no clue why her family is missing.

Dark Walking Simulators do a great job of presenting mysteries. In fact, I’d wager most great video game mysteries have large elements of Walking Simulators. Even the AAA titles that lean more into the mystery genre borrow heavily from Walking Simulators. Traveling in someone else’s shoes and interacting with your environment can make for a great mystery premise.

The Stanley Parable (October 2013)

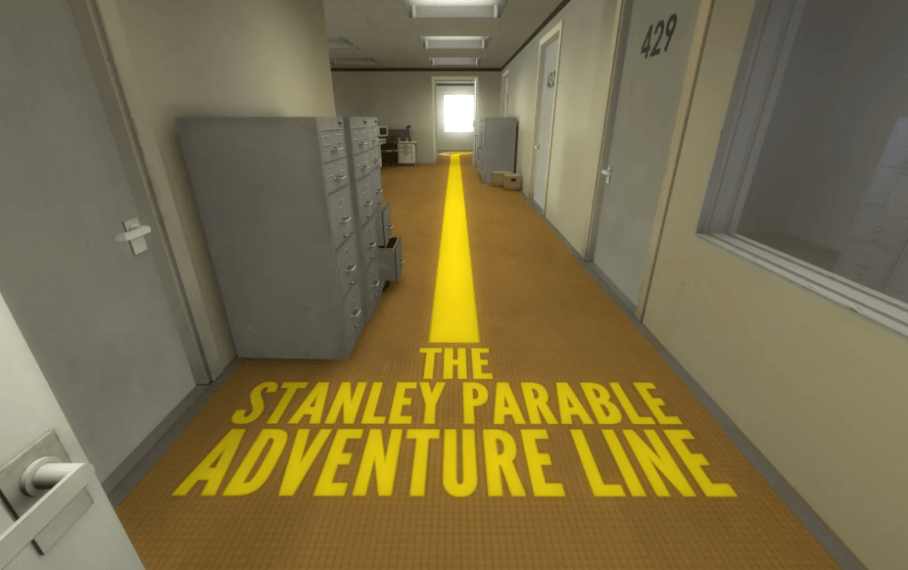

The Stanley Parable stands out in a group of video games that stand out. This Walking Simulator challenges preconceived notions about video games with a thick coat of sarcasm. Developed by Davey Wreden and William Pugh, The Stanley Parable tackles themes like choice in video games and fate/pre-destination. British actor Kevan Brighting narrates while the silent protagonist (Stanley) conducts a day at the office. As you can see in the image above, Stanley may follow the adventure’s line, or he may contradict The Narrator’s directions, which, if disobeyed, will be incorporated into the story. Depending on the choices made, the player will encounter different endings before the game resets to the beginning.

The Stanley Parable proves that Walking Simulators can strike a chord with “hardcore” gamers. The Stanley Parable crossed over into mainstream video game culture. Developer Davey Wreden has gained a following, and his follow-up game, The Beginner’s Guide, actually deals (in part) with Wreden’s struggles with success. Showrunner Dan Erickson cited The Stanley Parable as an inspiration for Apple+’s Severance.

The Static Speaks My Name (August 10, 2015)

While the previous games on this list have dark themes, The Static Speaks My Name is the first true horror video game.

Quick trigger warning: The Static Speaks My Name includes self-harm. If you’re sensitive to the subject of self-harm, feel free to skip this entry to our next one.

In The Static Speaks My Name, players assume the role of Jacob Ernholtz, a man who has committed suicide by hanging at the age of 31. We start as an amorphous blob in a dark void until we inhabit Ernholtz during his last day. We awake in his dimly-lit apartment with boarded-up windows and doors as he performs a series of menial tasks, including using the restroom, eating breakfast, and chatting with online friends. Exploring Ernholtz’s apartment reveals that he’s obsessed with a painting of two palm trees and its painter, Jason Malone. Locked behind a bookcase, we find Malone in a cage. The player has the option to unlock the cage or electrocute Malone. We’re finally presented with the task to go to a small closet with a noose.

Yowza! The Static Speaks My Name is trippy in every sense of the word. Jesse Barksdale developed The Static Speaks My Name in a 48-hour game jam. I’ve participated in a few board game jams, and you can encounter some messed-up concepts during one of these events. I would’ve liked to have seen Barksdale’s creative process for The Static Speaks My Name during these 48 hours. This is a haunting game. I’ve only chosen the electrocute option once, and Malone’s blood-curdling screams invaded my dreams for a few days. Yikes!

We included the exact date The Static Speaks My Name was first released because our next entry in this list was released the next day. This week in August was a great week for Walking Simulators.

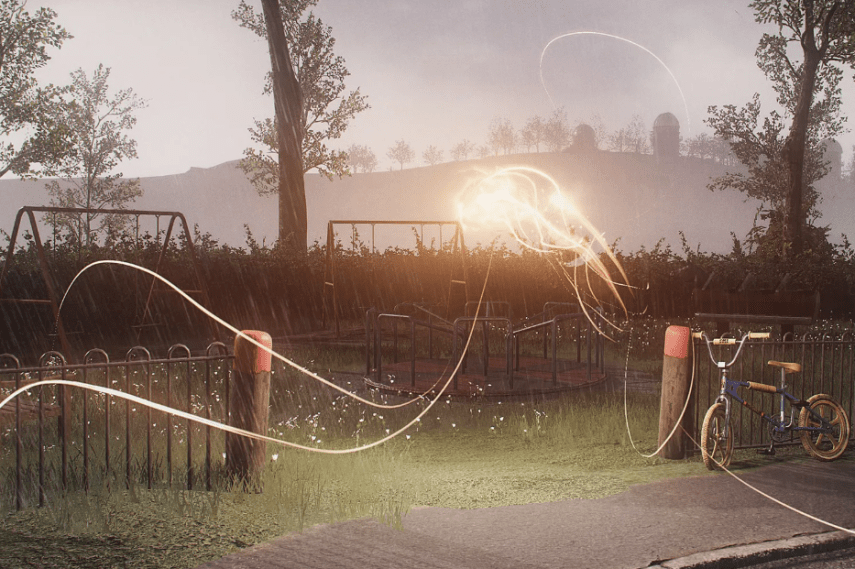

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (August 11, 2015)

Fresh off their hit Dear Esther, The Chinese Room takes the mysterious disappearance of people from the scope of a family in Gone Home to that of an entire English village’s citizens in Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. Players assume the role of Katherine “Kate” Collins, which is funny because Gone Home’s protagonist was named Katie. Set in 1984, Dr. Kate Collins and her husband travel to the fictional Shropshire village of Yaughton. Players can interact with floating lights throughout the world, most of which reveal parts of the story.

Feel free to turn on radios, answer the phone, and test the power switches as you unearth why an entire English village’s people vanished. Could this be the beginning of the Rapture and the end of days? Or has some mysterious fate only affected this one village? You’ll have to play Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture to find out.

That Dragon, Cancer (January 2016)

Get ready to reach for the tissues. This next entry is a tear-jerker. Created by Ryan and Amy Green, Josh Larson, and a small team under the name Numinous Games, That Dragon, Cancer is an autobiography based on the Greens’ experience raising their son Joel, who was diagnosed with terminal cancer at twelve months old. Though given a short time to live (four months tops), Joel survived for four more years before succumbing to cancer in March 2014. That Dragon, Cancer harkens to the age of point and click games–see, point and click games are closely related to Walking Simulators–and uses the medium of pointing and clicking to experience the Greens’ lives through interactive storytelling.

That Dragon, Cancer illustrates a video game’s storytelling potential. At first, Ryan and Amy developed the game to relay their personal experience with Joel while they were uncertain of his health, but following his death, the Greens reworked much of That Dragon, Cancer to memorialize and personalize their time and interactions with Joel for the player. Joel Green may have had a short life, but That Dragon, Cancer ensures he won’t be forgotten.

it’s always monday (November 2016)

I’ll start this write-up by commenting on it’s always monday’s title. I love its use of all lowercase letters. Yes, Monday is supposed to be capitalized, but the lack of capital letters gives the impression of words in the middle of a sentence. Brilliant. I debated including it’s always monday on this list. To put it mildly, it’s always monday is surreal.

Players assume the role of an office worker who, as the game’s title implies, is stuck in a loop of perpetual Mondays. My bad…mondays. Frequently, you’ll find moments where a coworker is cut into slices. The player character will freak out–naturally–and then notice a pizza on the conference table and comment, Today’s a pizza day. Score! What? I often wonder what it’s always monday’s overall message is supposed to be. Perhaps we’re supposed to feel trapped in a malaise where we want the character to feel something. Anything. But it’s always monday’s workplace offers plenty of bizarre occurrences that run counter to the mundane.

What Remains of Edith Finch (April 2017)

What Remains of Edith Finch borrows concepts from Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and applies them to an interactive video game where we follow the titular Edith Finch explores her family home. Like Marquez’s work, What Remains of Edith Finch ventures into magical realism. The game’s narrative works as an interconnected anthology series, and it’s all the better for it. I don’t know which member of the Finch family’s stories I like best. What Remains of Edith Finch is a triumph of video game storytelling. Giant Sparrow took everything they learned from The Unfinished Swan to create a singular gaming experience.

I could go on about What Remains of Edith Finch, but I’ve discussed it in the past. Giant Sparrow even made our 3 List of 3: Video Games as Art post. That was another shameless plug for one of our previous lists. You should check it out.

Walking Simulators in the 2020s: Exit 8

Walking Simulators fizzled out after 2017. I don’t know if the backlash of these games reached a fevered pitch or if the designers who make these games needed time to create something new. Death Stranding was released in 2019. To date, it may be the closest a AAA game has come to a Walking Simulator. It certainly incorporates a lot of Walking Simulator concepts into its gameplay. But our lack of Walking Simulators in the early 2020s can be attributed to the pandemic.

All video game struggles in the early 2020s, but we’ve seen a resurgence of Walking Simulators since 2022. Exit 8 has a premise similar to the Backrooms. Players explore the liminal space of Japanese subways. I’m writing this post in June, but by the time this post goes live, a live-action film based on Exit 8 should have been released. Walking Simulators have gripping stories and an avid fan base. I can’t wait to see what this video game genre has in store over the next decade.

If you’ve made it this far, you’re awesome. We all know it. Be sure to comment on your favorite Walking Simulator or an idea of a better name for this video game type. Thank you for reading, and wherever you are, I hope you’re having a nice day.