Last year (2024), I shared that I was diagnosed with ADHD and autism. Before that diagnosis, I didn’t know that someone could have ADHD and autism. This is a thing, and it’s called AuDHD (or AUdHD). As an older person (I won’t divulge how much older), I’m considered late diagnosed.

I didn’t think to get checked if I had autism until after my youngest daughter was diagnosed. This tends to happen for late-diagnosed people. Autism is hereditary. I’m nowhere near the only one in my family who could be diagnosed as autistic, but autism is a spectrum. Late-diagnosed people tend to be on the low needs and high masking end of the spectrum. Masking is the ability for autistic people to mimic neurotypical people’s behavior. So, I had a lot of experience “pretending to be normal.” It’s exhausting.

My parents, specifically my mom, had an idea that I may be autistic, but they never had me tested. Since my diagnosis, I’ve been playing back my personal history and reading literature and consuming other media about both ADHD and autism. That made me wonder how well certain media portray ADHD and autism.

Hey, hey! Kyra Kyle here. It’s Potpourri Friday, and we’re starting a brand-new series that could become a regular fixture: Autism Representation. Let’s begin with a series and character that most people know about or have seen, Sheldon Cooper from The Big Bang Theory.

Some of you may have let out an audible groan. While The Big Bang Theory may have given geek culture some much-needed shine a couple of decades ago, the show reinforced stereotypes and made fun of the geek culture it claimed to support. The live studio audience didn’t help. They expected The Big Bang Theory to make fun of the show’s “geeks,” and the showrunners obliged.

Before we get started, I need to cite a couple of disclaimers. First, I haven’t watched any of the Big Bang Theory spin-off shows. Yes. There are multiple Big Bang Theory spin-offs; there’s one scheduled for release later this year. This post will only concern itself with The Big Bang Theory version of Sheldon Cooper. Second, The Big Bang Theory ran for 12 seasons. 12 seasons! That’s almost 300 episodes. Most likely, every point I make may have a counterpoint. While not as bad as Friends, more than a decade on television turned each character of The Big Bang Theory into a walking contradiction. And now I have Green Day stuck in my head. Great.

My knee-jerk reaction is that Sheldon Cooper is nowhere near a “good” representation of autism, but on closer inspection, he may not be the worst. Okay. Sheldon is the worst (in terms of a person) a lot of the time, but to paraphrase Season, Sheldon may have an autistic sliver lining.

Autistic Stereotype

As I said in the intro, The Big Bang Theory loves stereotypes. It paints its characters in the broadest of broad strokes: the effeminate Asian (Raj), the resident pervert (Howard) who happens to be Jewish and lives with his overbearing mother, the more street-smart than book-smart blonde who lives next door (Penny), and the autistic-coded Sheldon Cooper.

Sheldon never mentions autism or being autistic. But could he be any more of an autistic stereotype? He loves trains. Check. He has robotic movements and an odd speech pattern. Double check. He struggles to understand social cues like sarcasm and experiences meltdowns. Triple check. He’s a savant with math and science. Quadruple check. In the show’s pilot, Penny dubs Sheldon one of those beautiful mind, genius guys. Just because an autistic person has a special interest (like math or science) doesn’t automatically make them an expert in the field of their special interest. I prefer Abed (from Community), who has a special interest in cinema and isn’t a very good filmmaker. Not every autistic person is a savant. I should know. I have plenty of special interests in which I stink.

Despite The Big Bang Theory’s over-reliance on stereotypes, many of these qualities that Sheldon has are autistic stereotypes for a reason. Many autistic men love trains, not so much autistic women. Come to think of it, that makes me wonder about my Uncle Paul. Autistic people can have odd and repetitive body movements with weird speech patterns. Most autistic people struggle with understanding social cues; the burden of navigating social interactions when one’s brain’s operating system runs counter to neurotypicals (people who aren’t neurodivergent) can lead to meltdowns. And since autistic people dedicate countless and tireless hours to their special interests, they can become experienced. And experience can be confused with natural talent when one doesn’t see the work that went into that experience.

We can conclude that Sheldon is a stereotypical autistic person. Before the past couple of decades, autistic researched revolved around cis, heteronormative, white men. Sheldon is a cis, heteronormative (to an extent), white autistic man. Autistic people like Sheldon exist, but Hollywood could present different kinds of autism on-screen.

East Texas Doorknob

Leslie Winkle (another scientist at Caltech where The Big Bang Theory gang works) calls Sheldon Cooper an East Texas Doorknob. That’s right and wrong. I was born in East Texas and can say that Galveston (where Sheldon was born and raised) is not East Texas. But Sheldon is a doorknob. Being autistic doesn’t prevent someone from being arrogant or misogynistic or a doorknob. Just look at Elon Musk.

On one hand, I like that The Big Bang Theory made Sheldon an unlikeable character, but he’s so popular (I guess being a jerk is “in”) that his character furthers autism stereotypes listed in the previous section, and in some people’s eyes, he’s become the default autistic person. I haven’t shared my diagnosis with a lot of people in my daily life, but whenever I do, there are a fair number of people who say, just like Sheldon. We’re not all East Texas Doorknobs. Some of us were just born in East Texas.

Despite his often negative portrayal, Sheldon Cooper proves that not all autistic people are angels. There’s an online movement that suggests that all autistic people are angelic and can do no wrong. Honestly, I’m tired of this trend and the “autism superpower” movement. We’re people with flaws. Some of those flaws can be obvious. I appreciate the Sheldon Cooper portrayal through the lens of him being a jerk and being called out on it. Sheldon doesn’t get called out on his bad behavior enough for my liking, and even when he does, he often suffers little to no repercussions, but I do like that he can be autistic-coded and be a jerk.

But Sheldon Cooper becoming the default autistic person is problematic. Not all autistic people obsess over trains. Like I said before, train-obsession tends to be an autistic man’s trait. Autistic women and autistic people who are gender non-conforming tend not to obsess over trains as often. Autistic women tend to get late diagnosed (like me), and often when they do get a diagnosis and share that with others, other people judge them because autism tends to manifest differently in women than it does in men, and these autistic women don’t act the same as autistic men or that autistic nephew everyone seems to have. Yeah. Because they’re women. An autistic woman isn’t usually going to act like Sheldon Cooper. For starters, most autistic women are more adept at masking.

Again, masking is the ability to mimic neurotypical behavior so others can’t tell you’re autistic. Autistic women tend to be better at masking, but the act of masking takes a lot of effort. One social interaction can drain one’s battery. This can lead to an autistic person having a meltdown or shutdown. We’ll discuss meltdowns and shutdowns later. Masking is another reason why autistic women tend to be diagnosed later in life. The autistic person becomes adept at hiding. Sheldon Cooper rarely hides his autism, but that doesn’t mean The Big Bang Theory doesn’t show social fatigue, and that’s where we may see some better autistic representation.

The 43 Peculiarity

The eighth episode of The Big Bang Theory Season 6 centers around Raj and Howard wondering what Sheldon Cooper does for an hour of unaccounted time. Sheldon plans his day to the second. Yes. This includes bathroom breaks. So, an hour of unaccounted time is out of character for him. Sheldon doesn’t share with Raj and Howard what he does during this hour (spoiler: he plays Hacky Sack), but he does share that navigating social situations all day is taxing, and he needs a break. This is a coping tool for autistic people. Hacky Sack may be a stim for Sheldon. Stimming is any self-stimulating behavior used as a means of self-regulating or coping with intense emotions. Anyone can stim. But Stimming tends to be associated with autism because autistic people have a more difficult time regulating their emotions.

It may be a huge stretch to suggest that Hacky Sack in this context is a stim for Sheldon. By its nature, one can’t schedule a self-regulating or coping behavior. One feels an emotion when one feels that emotion, and one must manage that emotion at the time it occurs. Most autistic people can’t schedule when to stim. I don’t care if your name is Sheldon Cooper. On a personal note, I stim by running my fingers over the hems of my clothing (I did this with a pillow when I was young), and when I’m out in public, I wear a ring with a built-in fidget spinner to discreetly stim. Getting back to Sheldon, Hacky Sack features repetitive movements, and the reason why Sheldon plays Hacky Sack fits under the umbrella of stimming. He needs relief from a world he doesn’t understand. He needs a break from the emotions of others that he can’t process.

Had Sheldon been tested for autism, a therapist could’ve taught him better coping skills. I know Sheldon often says that his mother had him tested, but he always prefaces that comment with I’m not crazy. My parents laughed whenever they used the “my mom had me tested” line with me; they even bought me a t-shirt with that phrase on it, but I was never tested (for autism) as a child either, or if I was, I wasn’t told of the result.

Knowing if one is autistic makes it easier to navigate a world that isn’t built for them. It’s like neurotypicals have Windows operating systems, and an autistic person runs iOS. Everyone else laughs at a Flash video. But Flash doesn’t run on my iOS brain. Knowing that sooner about myself would’ve allowed me to accept that difference sooner and learn better coping skills. Instead, I would shrink myself so others wouldn’t notice odd behaviors. I would often say something strange, and others would laugh, and I’d laugh along with them, not knowing that what I said or did was funny.

We see Sheldon attempt to fit in with the crowd in the final episode of Season 4. During the show’s cold open, the gang laughs about how Leonard can’t process dairy. Penny likens Leonard (whenever he eats dairy) to a gas-filled Macy’s Day balloon. Sheldon promptly corrects Penny. Macy’s Day balloons are filled with helium, while Leonard produces copious amounts of methane. The table guffaws. Sheldon doesn’t understand why. He was stating a fact, but since everyone else laughs, he mimics their behavior. So, Sheldon masks during this occasion. And on occasion, he can show a surprising amount of empathy.

Letting Go of a Pen while Your Favorite Pen is Safe in Your Pocket

Sheldon tends toward being self-centered. This is part of him being an East Texas Doorknob. But he can be empathetic. Season 8’s “The Comic Book Store Regeneration” is the episode where Howard’s mom dies. The actor who portrayed her (Carol Ann Susi) passed in real life, and The Big Bang Theory pays her a heartfelt tribute.

The main story centers around Stuart Bloom reopening his comic book store, hence the episode’s title, and taking furniture from Howard’s mom’s house. Howard doesn’t like that the furniture he grew up with is in a store. Howard gets a call from his aunt as Sheldon tries to teach him the trick Penny had taught him about letting go of things that trouble you by letting go of an imaginary pen. After Howard’s aunt tells him the news that his mom has died, Sheldon asks to say something. The others try to dissuade him. This is Sheldon we’re talking about; he can’t possibly provide comfort. Eventually, Sheldon shares with Howard that when his father died, he didn’t have any friends to help him through the pain. Sheldon reminds Howard that he has friends who are willing to help.

From the outside, it may appear that autistic people lack empathy. This isn’t true. Like the operating system example I shared previously, autistic people can struggle with processing emotions and showing empathy. Often, it’s easier for autistic people to share their feelings with other autistic people. There have been multiple studies conducted of autistic people and neurotypical people attempting to communicate. When the two groups were segregated between autistic and neurotypical people, both groups communicated more easily. When the two groups intermingled, the group struggled to communicate. Dr. Damian Milton calls this the “double empathy problem.” Both groups can express emotions and show empathy, but when two groups of people have very different life experiences (living as an autistic person is very different than living as a neurotypical person), they will struggle to empathize with each other.

Meltdowns and Shutdowns

The Big Bang Theory doesn’t shy away from showing Sheldon having meltdowns (big and small) and shutdowns. Two major meltdowns/shutdowns come to mind (Sheldon and his loom and the one with Sheldon’s birthday party), so let’s discuss them. We’ll begin with Sheldon’s birthday party (Season 9, “The Celebration Experimentation”) because it’s the most straightforward and a good example of acceptance and understanding.

Penny, Leonard, and Amy threw Sheldon a birthday party, the first since his childhood. The sight of so many caring people in one room overwhelms Sheldon. He runs to the bathroom. The gang argues over who should check on him, and Penny wins the argument. She joins Sheldon in the bathroom, asks him about his emotional response, and instead of chastising him for ruining the party (or worse), she sits in the bathroom with him. She reassures him that if he needs to sit in the bathroom on his birthday, then that’s what the two of them would do. This is a good response.

I don’t know how many times I’ve seen an autistic shutdown treated like it’s the worst thing in the world. At the very least, the autistic person would be made to feel bad about ruining a social gathering like a birthday party. This could be because this is an example of a shutdown and not a meltdown. Media often shows autistic people having meltdowns because it’s more dramatic. The scene will devolve into others restraining the autistic person and/or injecting them with a sedative. I’m looking at you, The Unbreakable Boy, and Sia’s Music. Scenes like these in real life lead to someone, usually the autistic person, getting harmed.

I like how The Big Bang Theory handled the previous shutdown, and I like that the show included a shutdown. Many autistic people have shutdowns more than or instead of meltdowns. But meltdowns do happen, and the one where Sheldon uses a loom (from season 1, episode 4 of The Big Bang Theory) is the first one the show addresses. Coincidentally, the opening moments of this episode create the show’s first anomaly. Sheldon states that if he ever creates a time machine, he’d just go back in time and give it to himself. Leonard says, Interesting. Why does Leonard say that? Going back in time with a time machine and giving Sheldon the completed device was part of Leonard signing the roommate agreement. He already knows this. Again, the show was on the air for 12 years. Contradictions abound. I digress.

Let’s get back to the fourth episode’s setup. Sheldon gets fired for insulting his boss, Dr. Galblehouser. Sheldon’s an arrogant East Texas Doorknob, so that tracks. At first, Sheldon handles the situation well enough. He starts by trying to fix everyone’s scrambled eggs. Odd, but okay. When eggs are a dead end (they’re as good as they’re ever going to be), he switches to breeding luminous goldfish (note: the episode’s title is “The Luminous Fish Effect”). Sheldon claims his goldfish will eliminate the need for nightlights. But why stop at fish? Glow-in-the-dark tampons. And the word luminous leads him to the word loom, and he starts weaving ponchos. This break causes Leonard to call Sheldon’s mother.

This is a comical, over-the-top meltdown. It may be more of an existential crisis, but again, I digress. The point of mentioning this moment isn’t necessarily the way the meltdown is shown (as I described before, The Big Bang Theory never showed a dramatic meltdown with someone getting restrained or sedated), but the more important takeaway is how others treat Sheldon during this meltdown or existential crisis. When Sheldon asks why his mother is in his apartment, Mrs. Cooper states that Sheldon’s little friend (Leonard) is concerned about him. Sheldon insists that he isn’t a child and then storms off into his room.

The idea of infantilization is a real thing in the autistic community. Just because an autistic person displays an overly emotional response doesn’t negate their status as an adult. Adult autistic people do exist. Heck. So many of us are diagnosed later in life. Autism isn’t just a children’s disorder. Sheldon undermines his claim that he’s an adult by frog stomping into his room and claiming that no one’s allowed inside his room, but again, no matter how ridiculous Sheldon behaves, he maintains his status as an adult. We’ll see how this episode handles the aftermath, but first, I’d like to examine the exchange between Mrs. Cooper and the rest of the gang. This exchange provides some insight into Sheldon’s childhood.

Mrs. Cooper quotes her dead husband by saying that you have to take your time with Sheldon. We see Penny do this in the birthday scene we discussed. That’s good. But Mrs. Cooper also alludes to Sheldon being a burden, and that’s something that often happens with autistic children. Mrs. Cooper, in not-so-many words, suggests that Sheldon is her cross to bear. We see this again in The Unbreakable Boy. That movie may top Music as the worst representation of autism. The father (who is the point-of-view character) views his son Austin (who has autism and brittle bone disease) in his good moments as a beacon of hope and in his troubling moments as the family’s burden. More specifically, his cross to bear.

No one likes being considered a burden. From personal experience, it’s dehumanizing for another person to boil someone down into an obstacle one must overcome, especially when that person is a parent. The Big Bang Theory flirts with this idea on more than one occasion, mostly through Leonard and Sheldon’s relationship. Autistic people can’t help how they are. They can use more understanding. What we get in “The Luminous Fish Effect” (Season 1, Episode 4) is Sheldon’s mother breaking down and treating him like he’s a child. While this reaction proves effective (Sheldon gets his job back), it infantilizes a grown man. Was there another option? Maybe. Still, I prefer the moment with Penny and Sheldon in the bathroom. She showed that she cared for him and reinforced that she wanted to celebrate his birthday with him in some fashion.

I still wonder if Penny is guilty of treating Sheldon like a child in this moment, and she could give him a moment to leave the bathroom on his own accord, but this is a better reaction than what might have happened when Sheldon was ten-years-old or younger.

When Facial Expressions Don’t Match Someone’s Tone

I mentioned Sheldon’s difficulty in recognizing sarcasm at the beginning of this post, but let’s dig a little deeper. Sheldon’s trouble with reading sarcasm (without a sign) stems from when someone says a phrase one way, but the person’s facial expression doesn’t match what they’re saying. Season 10, Episode 6, “The Fetal Kick Catalyst,” does a great job of punctuating this point.

Sheldon throws a “practice” brunch by inviting a group of C-list friends: Bert the Geologist from CalTech, Mrs. Petrescu, a Romanian immigrant who lives downstairs and who is just learning English by watching television, and Stuart Bloom, the comic book shop owner. Sheldon lets it slip that the group is their “practice” group of friends. As a result, Stuart gets his feelings hurt and asks, “So, I’m like a lab rat before your real friends come over?” Sheldon gets confused and says, “Your words sound reasonable, but your face looks angry.”

Amy tries to smooth things over with Stuart by saying, “Stuart, you know you’re one of our favorite people,” but this continues to baffle Sheldon, and he says, “See, now, you look sincere, but your words are completely false.” Stuart hangs around for brunch, presumably waiting for an apology, and when he doesn’t receive one, he gets up to leave, stating that he doesn’t think Sheldon sees him as a friend and that Sheldon excludes him. In another rare moment of empathy, Sheldon confides in Stuart that he often feels excluded.

All’s well that ends well, but the difficulty of reading what someone says when their facial expression doesn’t match a person’s tone is an issue for autistic people. I’ve had difficulty noticing sarcasm because that’s the point of sarcasm. Someone says something in a way that’s incongruent with their facial expression and what they really mean. Sheldon mentions plenty of times that he wishes people would just say what they mean, that would save a lot of time. That’s relatable if Sheldon wasn’t comically bad about reading emotions.

Difficulty Reading Emotions

Like I said, Sheldon is comically bad at reading others’ emotions. The cold open of Season 10, Episode 14, “The Emotion Detection Automation,” hammers this home. Raj bemoans his lack of a dating life but tries to remain positive. Raj’s words and the way he speaks suggest that he’s fine, but he slumps his shoulders and mopes up the stairs. Again, I said that I can struggle with this if the signs are subtle; The Big Bang Theory goes with huge swings. Even I could tell Raj was depressed.

This interaction prompts Sheldon to join a study where they give him a device that can read others’ emotions. The scene devolves into Sheldon calling everyone out when their facial expressions and what they say don’t match. This leads to another shutdown for Sheldon. He runs to his bed, and Amy must remind him that he’s learning to read others’ emotions. Autistic people can learn how to read people better, especially if they spend plenty of time with the people in question. Would I say this is good autistic representation? Sort of. The Big Bang Theory tends to ham-fist any link with Sheldon and autism for comedic effect. The show is a comedy first and foremost. But underneath the layers of sarcasm lies some truth.

Time Blindness

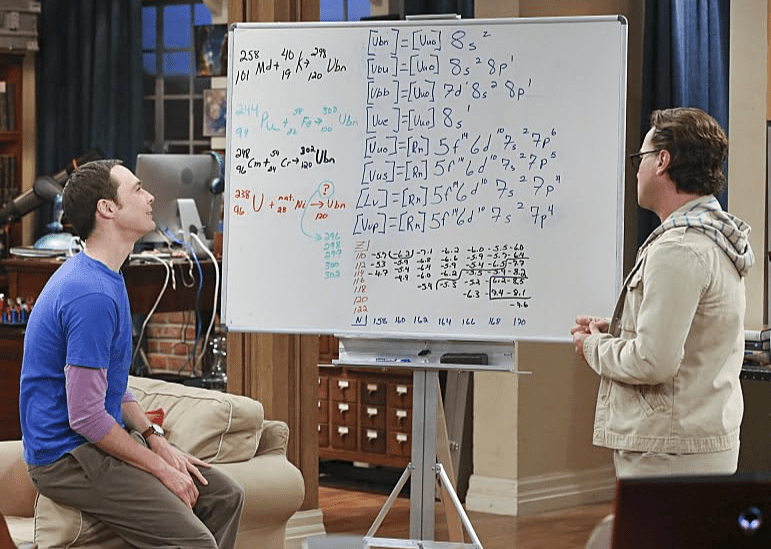

Let’s continue with some quick examples of potential autism representation with Sheldon Cooper, beginning with time blindness. Season 7, Episode 6, “The Romance Resonance” cold opens with Sheldon working at the Cheesecake Factory. Evidently, he’s been working on his physics project for some time, because the cold open’s zinger is Sheldon asking, When did we get to the Cheesecake Factory? The episode continues with Sheldon working on his project, presumably having not eaten at the restaurant, and not speaking for countless hours. Eventually, Sheldon breaks his silence by celebrating a scientific breakthrough and how amazing he is. Sheldon and his brain. Yeah!

While I can’t relate to being amazing, I have lost several hours to a single project. My wife and kids have checked on me numerous times, asking me if I’ve eaten at all during the day. Typically, I answer no. This is time blindness. While anyone can experience it, neurodivergent people (mostly autistic people or ADHDers; I’m both, so double-whammy) are prone to time blindness. This is one of the reasons why some people believe Sir Isaac Newton was autistic; he forgot to eat and needed to be reminded by his loved ones.

Parallel Play

During Season 8, Episode 3, “The First Pitch Insufficiency,” Sheldon, Amy, Leonard, and Penny go on a double date. Leonard and Penny’s relationship has hit the skids, and Sheldon suggests that he and Amy are the better couple. While in the car, Leonard accuses Sheldon and Amy of sitting in the same room and not even acknowledging the other one exists for hours. Sheldon explains that he and Amy are parallel playing. Leonard scoffs at the explanation, likening it to something toddlers do (which is infantilizing Sheldon), but this is something adults can do as well. Like stimming, neurotypicals can parallel play too, but autistic people are more likely to engage in this activity for hours.

I’d like to claim that I was the first one in my family to learn about this, but after my diagnosis, my wife read an article about autistic people and parallel play. Autistic people are comfortable being in the same space as their loved ones, even if they never speak or interact for several hours. Autistic people just like being in a space with the ones they love. My wife noticed that I did that on occasion, and ever since reading that article, she’ll ask to parallel play.

Echolalia, and Vocal and Auditory Stimming

During Season 9, Episode 10, “The Earworm Reverberation,” Sheldon gets an earworm stuck in his head. In classic Sheldon fashion, he takes this to the extreme and plays the tune over and over again until he can figure out what the song is and why he’s singing/humming/playing it. Sheldon’s actions are played out for laughs (when Penny takes away Sheldon’s keyboard during the night, he switches to playing a tuba) and lead to Sheldon realizing he wants to get back together with Amy.

Sheldon’s response is autistic adjacent behavior. Autistic people can get hyper-fixated on sounds, playing them over repeatedly. This can be vocal stimming (with music or speech) or can take the form of echolalia (with sounds and phrases). I’m guilty of both. I have perfected my meow and throwing my meow. My wife will sigh and complain that the cats need something, when I was the one who was meowing. Meow!

Autistic people can also listen to the same piece of music ad nauseum (auditory stimming), and it can bring them comfort. I listen to sitcoms when I fall asleep. How do you think I “watched” The Big Bang Theory so many times? The laughter soothes me. But again, I say that Sheldon’s response to getting The Beach Boys’ “Darlin” stuck in his head is autistic adjacent behavior because of why he does it. This song was a plot device and played for laughs. Autistic people will participate in these actions because they help regulate their emotions.

I’ll throw in one bonus term: palilalia. Sheldon doesn’t display this trait to the best of my knowledge. Palilalia is when a person repeats themselves or mouths something they’ve already said. Before my autism diagnosis, my wife called it the “Japanese thing.” Occasionally, I would mouth what I had just said, which would look kind of like an English-dubbed Japanese movie, as in the character would finish speaking, but their mouth would keep moving. My wife turned giddy when she saw our youngest daughter doing the same thing. She said, “She inherited it from Mapa.” Our daughter did inherit palilalia, but not in the way we first thought.

Fun fact: How many edits of this post do you think it took me to realize that one of my opening phrases (in most of my Geekly posts) includes hey, hey? That may be a written version of palilalia. Hey, hey! feels good to my ears because I like the repetitive sound. Oh no! My name’s Kyra Kyle. Moving on.

Knocking Exactly Three Times: Rhythmic Stimming

Sheldon knocks three times on people’s doors throughout The Big Bang Theory’s 12 seasons. This can be viewed as rhythmic stimming. The rhythm of knocking three times soothes Sheldon is established in the show, especially in Season 9, Episode 2, “The Separation Oscillation,” when after denying himself knocking three times on Amy’s door (to punish her for breaking up with him), Sheldon knocks on a table to achieve the effect. Sheldon comments, “So tables work too, good to know.” Even though knocking on a surface three times in a specific rhythm is a soothing mechanism (stimming) for some autistic people, I can only classify this as autistic adjacent behavior for Sheldon.

There’s a narrative reason why Sheldon does this. The show explains this odd behavior in Season 10, Episode 5, “The Hot Tub Contamination.” When Sheldon was 13 years old, he walked in on his father having sexual relations with a woman who wasn’t his mother. Ever since that moment, he has knocked that many times to make sure people on the other side of the door can get decent. Again, autistic people don’t need something traumatic to trigger such behavior.

Note: While I haven’t watched Young Sheldon, I’ve heard that the show may have changed the origin of Sheldon’s triple knock.

Fails to Notice Others’ Lack of Interest

I could’ve picked numerous moments where Sheldon drones on about one of his special interests, no one else cares, and he doesn’t pick up on any social cues. A close contender is Sheldon discussing whether he should get an Xbox or PlayStation at the dinner table, and Amy just wants him to pass the butter. But I decided to go with Season 10, Episode 15, “The Locomotion Reverberation.” In a true over-the-top Sheldonism, he talks about an upcoming trip where he’ll get to be a train engineer and drones on for what must be a twelve-hour timeframe. Amy brushes her teeth, goes to bed, and lies awake all through the night while Sheldon never stops talking. The scene ends with Sheldon saying that it’s time to go to work.

While I have moments where the train needs to reach the station for a topic, I’ve never been that bad. I don’t think. I’ve never filibustered with my special interest, although now that I said it, I think an autistic politician could pull off a mean filibuster. Moments like this, where Sheldon speaks for twelve straight hours, make him seem fictitious. Have any of my autistic people been able to talk about their special interest for twelve hours uninterrupted? Let us know in the comments. I think my vocal cords would need a break.

Final Thoughts

Speaking of breaks, let’s end this deep dive with that final point. The Big Bang Theory is a comedy. It exaggerated stereotypes for comedic effect, and Sheldon was the autism stereotype. Sheldon Cooper was never officially dubbed autistic. If he were, The Big Bang Theory may have had to hire an autism consultant like they did physics consultants. Numerous shows and films have taken this route. If you don’t commit to a character as autistic (and instead code them as autistic), you can save money and time and avoid backlash like The Unbreakable Boy and Music. Plausible deniability at its finest.

To the best of my knowledge, Jim Parsons isn’t autistic. In the future, we should strive for more representation that includes the people who are being represented. There is a growing number of autistic actors who could take on roles like Sheldon Cooper. Perhaps we’ll see a show like The Big Bang Theory that includes a comedic autistic actor. We need more representation of autistic women and autistic people of color. Autism isn’t a monolith. If you’ve met one autistic person, you’ve met one autistic person. They’re not all like your 12-year-old, white nephew. They’re not all Sheldon Coopers.

Is Sheldon Cooper a good representation of autism? No, and occasionally yes. For the most part, Sheldon Cooper is a comedic autistic stereotype, concocted by people who don’t have autism. He embodies a lot of the tropes of a young white autistic male, down to his sometimes childish mannerisms. But The Big Bang Theory’s quieter moments reveal a character who flirts with authentic autistic representation.

Wow! That was our first media deep dive. I don’t know if these will get this long; few shows run for 12 seasons. Hopefully, I didn’t ramble too much. Thank you for reading, and wherever you are, I hope you’re having a great day.